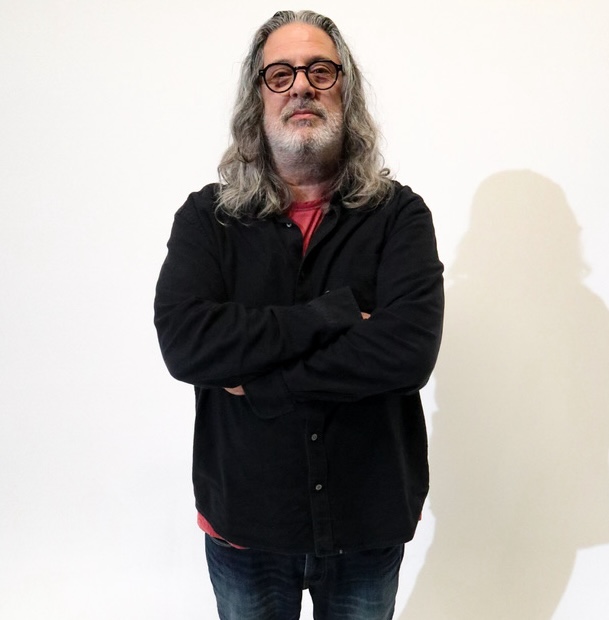

BY KAREN BLISS

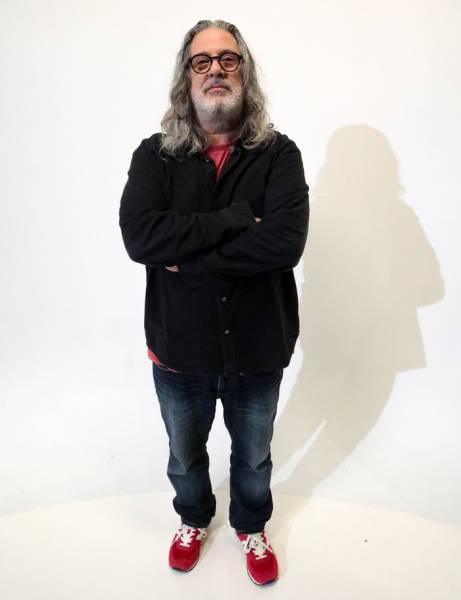

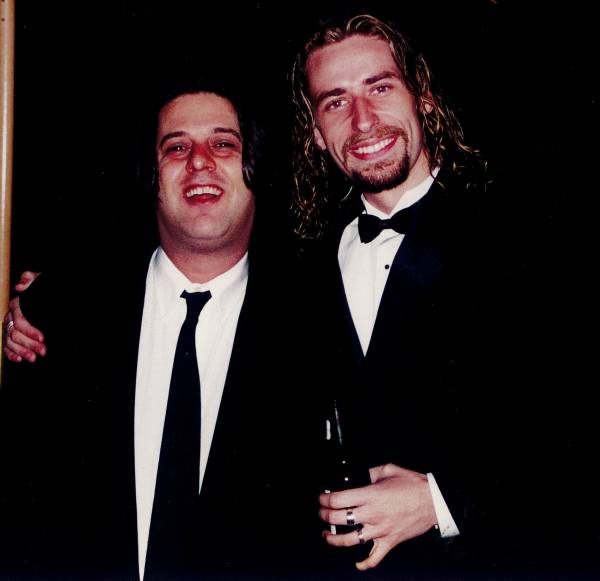

“We couldn’t have started a label at a worse point in history,” reflects Jonathan Simkin, president of Vancouver indie 604 Records, whose first signings in 2001 were rock band Theory of a Deadman and harmony-driven pop band Marianas Trench, both still going. The “we” is Chad Kroeger, frontman for mega-selling rock band Nickelback — Simkin’s long-time client in his law practice, Simkin & Co. Law Corporation, who he has represented since the mid-90s.

Kroeger is co-owner and co-founder with Simkin in The 604 Group, which today includes the alternative label Light Organ (started in 2010), Comedy Here Often? label (started in 2016), ambient/instrumental/lo-fi label Intraset (started in 2021), and 604 Podcast Network (created last year to expand upon the original Comedy Here Often? Podcast). They employ about 40 people and have another 10 or so on contract. A handful of people work out of Toronto and they are thinking of hiring more.

“I called it 604 because because Lyor Cohen [then head of Island Def Jam Music Group, which had a 50% stake in Roadrunner] who gave us the money in the first place, really wanted us to open in New York or LA and we were trying to explain to him, ‘No, no, no, we want to be the big fish in this small pond because there’s so much talent out here,’” Simkin tells Making Noise. “So naming it 604 was kind of a fuck you to Lyor — a funny fuck you. But it was like, “Hey dude, we’re not going anywhere.”

Simkin also runs Simkin Artist Management, with a genre-spanning client roster from Marianas Trench, Coleman Hell, Andrew Hyatt and The Zolas to graphic artists like record-breaking Mad Dog Jones, whose Replicator NFT sold for $4.1 million USD and Forever Mart made $1 million in a single day.

He managed Carly Rae Jepsen for five years — still on 604 Records — during what he refers to as the “life-altering” “Call Me Maybe” period, whose proceeds enabled them to expand the 604 operation, purchase property and build a soundstage and recording studio. The production facility is incorporated into so many aspects of 604, such as music video shoots and the filmed 2023 Simon King comedy special, As Good As Or Better Than, which was picked up by 800 Pound Gorilla.

Last year, Simkin added a digital art division and marketplace, 604 Infinite, to his business portfolio. He will soon be launching a new podcast called I Hate Simkin on the 604 Podcast Network. Guests so far include Nickelback’s long-time agent Ralph James, Kilometre Music Group’s Mike McCarty, CCS Rights Management’s Jodie Ferneyhough, and Nickelback bassist Mike Kroeger.

It’s all a bit “shocking,” Simkin says, the success that he’s had, considering he “accidentally” fell into the music business in the early 90s after starting as a criminal and refugee lawyer. He discovered he an ear for finding talent and securing recording agreements for artists, who went on to have major success, Nickelback, of course — one of the biggest-selling rock acts of the last 20 years — sibling duo Len, with their perennial placement “Steal My Sunshine,” and rock band Default, led by now country star Dallas Smith.

“I’m not even saying it with false modesty; it freaks me out,” Simkin says. “It’s grown in ways I’d never ever imagined or intended. I was never that guy who’s like, “’I wanna build the biggest label.’”

In a candid conversation with Karen Bliss, Simkin talks about building 604, Kroeger’s role, how the “Nickelback hate” influenced 604’s expansion, the new comedy, ambient and digital art divisions, and his view on “the Hedley thing.”

You admittedly have a bit of a reputation in this business, and you joke that you are an a-hole. You do speak your mind.

The thing is most people don’t succeed as artists in this business. Maybe less than 1%. So, for a lot of people, if that part of their career doesn’t work out, they’re like, “Well, I love music so much. I want to be involved somehow. I’m going to become an entertainment lawyer or I’m going to start a record label or I’m going to get a job at a record label.” That wasn’t me at all. This was not part of my planned trajectory and that informs a lot of my career, once I was in the music industry, because I didn’t have that baggage. I didn’t have any bitterness because my career didn’t work out as a singer. So, I’ve always just reacted to things with common sense and with honesty. I think, that’s one reason why I freak out a lot of people in the businesses because if something stinks to me, I’m going to say it stinks. Doesn’t mean I’m right, but it means I’m honest. Whether it’s being vocal about the Hedley thing, if I see something I don’t like, I’m gonna say something about it. I’ve never given a shit what people think about that.

That said, you’re close to a 30-year relationship with Nickelback. You’ve been partners with Chad in 604 since 2001. You have managed Marianas Trench since the start of their career and Carly Rae Jepsen is still on the label. If that view of you was accurate, I don’t think those people would be working with you this long. I’m trying to say, you have a softer side and do care.

I don’t disagree with that. I think once people get to know me, for the most part, they do like me, although that’s not really what I’m out for. I mean, everybody cares what people think of them, even if they say they don’t. But what I’m really saying is I don’t really care what the industry, as a whole, thinks of me. That, I’ve never cared about. Do I care what my employees think? Of course, I do. Do I care what my children think of me? Of course I do. Do I care what the artists on the label think of me? Of course. And, that’s come up in various ways.

For example?

Like, when the industry took such a downturn after Napster, Chad and I had just started the label. We couldn’t have started a label at a worse point in history. The first record we put out was that Theory of a Deadman record [2002, eponymously titled] and we had some hard decisions to make, including do we want to do 360 deals [an all-encompassing recoupment agreement], which became the standard? Chad and I had a lot of very serious talks about that and we decided not to do it. The reason was simple: I love working in the music business, but I also love sleeping at night and I didn’t want our artists to hate our guts.

That was one of the reasons I got out of being everybody’s lawyer because when I was doing these 360 deals for bands, I’d always tell them, “I don’t think you should sign this. I think you’re going to come to regret it” and they would sign it anyway. I knew that in five years that artist was going to come back to me and say, “Why the fuck did you let me sign that shit deal?” And I would’ve said, “Well, I told you not to sign it.” I was starting to feel like I was an accomplice to a crime doing these 360 deals. And there’s just an example.

I have real definite sense of fair play and right and wrong that I always try to employ. I think my artists always agree with that. “Jonathan can be a hard ass about stuff and he can be stubborn about stuff, but he gives a shit that people are treated fairly” and that’s something I’m proud of. I think our deals are fair. I think the way we do business is fair. Again, I love making money in the music business, but I would never want to do it in a way that I would have to start questioning myself.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s talk about this holistic set up you’ve built out west. You still practice law. 604 is 20 years strong. You have your management company. Under 604, you added another label, Light Organ, in 2010. And then 10 years ago did a major expansion, purchasing a building and starting a studio and soundstage. Is this the house that “Call Me Maybe” built?

So, long before “Call Me Maybe,” I had always had that as a vision. It was a reaction to what I felt was too many middle persons in this business. Again, this goes back to me not coming from the music business and doing things as they make sense to me. I always said if we could control the means of production, that would really be something. I was always struck by something Berry Gordy said about Motown, which was, “We make the records in the back and we sell them out the front.” That really stuck with me. So, I had this vision of doing that.

It started with The Organ. They made a record that they decided they didn’t like and they came to me and said, “We threw the record away. Literally, they threw the masters in the river.” [Laughs] because they hated them. They said, “Look, you’ve got this space in the back of your building” — this was at the old 604 [a spot rented near Olympic Village] — “can we just set up in that room and record?” I didn’t have a choice at that point. I said, “Sure.” And they made that great record, Grab That Gun [2004]. That’s when I went, in my brain, “We need to have a studio.”

So when “Call Me Maybe” exploded [2012], I had the financial resources to purchase a building, which we did in the Railtown section of Vancouver. It’s our offices. We have a full-size soundstage; we have recording studios. It’s been amazing. It’s definitely one of the best things I ever did.

604 doesn’t have one distributor outside of Canada. You do deals for each artist. Why that approach?

In Canada, we’re Warner. And that makes us promiscuous when it comes to distribution in Canada because we have literally been with every Canadian distributor. Love being with Warner and love Kristen [Burke, WMC’s president]. With other territories, we decided after that first deal with Lyor and Cees Wessels [founder of Roadrunner], that we didn’t want to have general distribution outside of Canada. And the reason is simple. I didn’t want people putting out our records because they were contractually obligated to; I wanted people to put out our records because they love our records. And that’s why ever since then, we just do individual deals. So, Coleman Hell came out on Columbia, Carly Ray Jepsen came out on Interscope, My Darkest Days came out on Island Def Jam and Theory of a Dead Man on Warner.

Did you start Light Organ as your alternative label because 604 was essentially a rock label with acts like Theory of a Deadman, Thornley, My Darkest Days, even though pop band Marianas Trench was among your first signings?

Not really. People sometimes get confused when they look at 604 because there’s country, there’s rock and there’s pop. There’s a lot of different things and that’s simply a function of the fact that my taste is pretty diverse. There are labels who do one thing, but that was never what I wanted. I just wanted to find stuff I liked.

Then, why the need for Light Organ, then a separate comedy label and ambient label? Why not put everything under 604 if it’s so diverse?

Well, Light Organ was a direct reaction to all the Nickelback hate. It was getting to the point when Nickelback — when people were really at the peak of disliking them — that it was becoming impossible for us to work with alternative bands. And my experience as a lawyer was as steeped in alternative music. For example, I was a lawyer for Mint Records for two decades; I love that kind of music. But, we were finding that bands were turned off by the Nickelback link, especially since our biggest band at that point was Theory of a Deadman. So, if I had a 604 logo on a record and sent it off to college radio or to tastemakers, I might as well put a fucking swastika on it the way people were reacting to it: “Corporate sellout bullshit.” So I approached Chad and I said, “I’m really worried that we’re going to lose the ability to work in that world. Would you have an issue if I started another label under 604 that separates itself from 604?” And that’s why I started it. It was about the Zolas because they expressed some concern about that. I understood that. So Light Organ was a direct reaction to the Nickelback hate.

You started your newest label, Intraset, in 2021. Is there an untapped market for ambient music or is this just personal taste?

I don’t know if there’s a market. I rarely think like that. I’ve been good at business, but it’s been more intuition. Once I find a band, obviously my first question is always, “Who’s the audience and how are we going to reach that audience?” But the ambient thing was very much a function of the pandemic because I found myself alone in my office listening to ambient music and classical music because I can’t work if there’s music in the background with lyrics; it screws up my brain. So, I was listening to lots of ambient, lots of classical. Spotify has so many of those kinds of playlists, like “focus” or “studying,” and you’d look at these playlists and there’d be millions of followers on these songs that have millions of streams, and yet I hadn’t heard of barely any of these artists. And so, that got me thinking, “What an interesting concept that you’re marketing mood music, as opposed to marketing artists and personalities.” I just thought that was fascinating. Plus, I love the music. And I was like, “This seems like an interesting area to get into.” It was a bit of a whim at first, but then it started to have some success. So, we’re like, “Let’s keep going.” And that’s a label we’re really doing some interesting things with now in our space. We’ve done two ambient shows there, where we filmed and recorded. So, we’re going to be putting out live ambient albums with the accompanying performance film. Nathan Shubert is the first one we did.

Last year you launched a digital art division and marketplace, 604 Infinite, and did extraordinarily well before that, in 2021, with one of your management clients, Mad Dog Jones (then a member of 604 act Coleman Hell), during the NFT craze. Has the bottom fallen out of the NFT market now or is there still value?

NFTs definitely are in trouble. The thing is, I never really looked at it like that. I liked it because I love the possibilities with the art form. Full disclosure, I don’t own a single NFT; I don’t own a crypto wallet. A lot of people in that space are really devoted to the whole concept of decentralized banking and there’s a lot of political stuff that goes with that. That was never what I was about with me. If you walk into my office, I collect rock ‘n’ roll toys. To me, that was what it was about. I just found it fun and an interesting way for people to re-experience their favorite artists. So, is the NFT thing fucked up right now? Absolutely. But luckily the artists I work with, Mad Dog Jones, Fvckrender, Victor Mosquera, they saw the writing on the wall, even then.

So, let’s take Mad Dog Jones. Right now, we’re doing a clothing line with Puma. We’re doing something with the International Space Station. We’re continuing our work with Mercedes. He designed helmets for [race car driver] Lewis Hamilton. So, Michah [Dowbak], that’s his real name, was always very aware of that, that if we were putting all our eggs into the NFT basket, he might have a very short career. So right from the beginning, even when things were at their height with NFTs, we were furiously working to make sure that his career was going to be about more than just NFT. So, he’s doing great. We have tons of great stuff coming out. The fact that he broke the record for the highest-selling piece of art by a living Canadian was just a bonus. I feel very lucky to have been involved with that. He broke Jeff Wall’s record [of $3.7 million USD]. He sold his piece, Replicator for $4.1 million U.S. on Phillips auction house. Pretty crazy.

Let’s talk about Nickelback. You’ve been their lawyer since before they were signed. Last year was really their year. Canadian Music Hall of Fame at the Junos, the documentary premiere at the Toronto International Film festival, the new album, the tour, crossing into the country world, and just the enormous acceptance and love that people showed for them. How did you feel being along for that ride and watching all that in 2023?

Yeah, it was satisfying. When you’re on the inside, of course feels and is a lot different than it might appear from the outside. We’ve all gotten used to the shitty comments, but it still hurts on some level. I suppose, the reason it hurt the most, from my perspective, was that they’re the nicest guys. Say what you will about the music, if you like it or don’t like the music, I don’t care; music’s subjective, but it was the personal nature of some of the attacks that really bothered me. I just never fully understood where the venom came from. I think I understand it now more than I did at the time. So yes, of course, getting into the Hall of Fame, amazing; having a tour that did so well, amazing. It felt very satisfying. And I definitely mean that more in a personal way than in a business way.

I mean, I’m happy that the business side of it is great, but the truth is the business side of it for them has always been great. For a band who some people would call the most hated band in the world, they’re also the 11th biggest-selling musical act in history. Clearly not everybody hates them. People are just weird and vocal about it, but yes, it’s been a wonderfully satisfying year and a half or so. And internally we’ve all just been able to take a nice breath.

2012, “Call Me Maybe” became a massive unexpected global hit, but now it’s certainly an unexpected pop classic. Can you talk about that a little bit? It’s still getting licensed. [Jepsen and Tavish Crowe co-wrote it as a folk song, but then Josh Ramsay of Marianas Trench gave it a pop treatment. Justin Bieber and Selena Gomez heard the single on Toronto radio and tweeted about it. Jepsen then signed to Beiber’s then-manager Scooter Braun’s label, Schoolboy].

Yeah, it’s funny, isn’t it? When you go to law school, you think your legacy might be arguing a case in front of the Supreme Court that changes things. Apparently, my legacy is going to be a pop song, but it’s incredible. It was life-altering for so many people. In mostly good ways, but also in some bad ways — you know, more money, more problems, that kind of thing. But, financially, unbelievable what it did for the label and for the people involved. It wasn’t just Carly. Josh Ramsay co-wrote it and produced it, Tavish Crowe co-wrote it, and Dave Ogilvie mixed it. So, a lot of people in my world were part of that. What a moment in time. And, yes, it continues.

I don’t think a single day goes by that there isn’t at least one email about it, one offer about it. Now, it could be something goofy, I don’t know, a soap commercial in Poland. But, a lot of times it’s really amazing things. We just licensed it for the new Paul Thomas Anderson movie. Oh my God, that’s not even about the money; that’s just one of my favourite directors. So all these years later, I still have a lot of “wow” moments. It changed everything for the label. It enabled us to buy that building. People looked at us differently, I think. And it’s shocking that, to this day, it’s almost as active as it was 10 years ago.

You started a comedy label Comedy Here Often? before the Juno Awards reinstated the comedy album category after 34 years [it existed 1979-1984].

I had a bit to do with that. When I started CHO? and found out there had been no award since the Bob and Doug [McKenzie’s Strange Brew], I was horrified. I immediately started to advocate to CARAS [the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts & Sciences] about it, and also rallied the troops in the Canadian comedy world. But, to be clear, I was one of a number of people who went to battle on this. It was not just me, though I feel like I sort of got the ball rolling. [CHO? signing Andrea Jin won the award in 2022 for Grandma’s Girl].

Comedy records used to be hugely popular — Steve Martin, George Carlin, Richard Pryor — but first video, then the internet, and the way listeners could consume comedy, killed that. What made you think it was a good career step to launch a comedy label?

We have a producer on our label named Kevvy [Kevin Maher] who’s also with the band Fake Shark. As a side gig, nothing to do with the label, he was often producing comedy records. He was the go-to guy. He would be in our studio and I’d just be shooting the shit with him, “What happens to these albums when they’re done?” And he said, “Nothing really. They produce enough CDs to sell at shows. They submit it to SiriusXM, they put it on Spotify and that’s it.” And I said, “If you actually put some marketing money into some of these albums, I wonder what would happen.”

And so, he was producing a record for a West Coast comedian named Kevin Banner and I thought it was so funny, I said, “We should think about putting it out.” I wasn’t thinking of starting a comedy label; it was just like a one album thing. “Why don’t we try this?” And it went really well. It received substantial airplay on SiriusXM. And that was when I went, “This is something.” And that division has done really well. We have a regular show in our soundstage on the last Friday of every month that we record and film. The clips on the Comedy Here Often Instagram are mostly from those shows. We regularly get well over a million views.

The money, interestingly, in comedy, is more in [neighbouring rights] SoundExchange because of the SiriusXM play. Nobody streams comedy on Spotify. But when they get their play on SiriusXM, that can lead to some serious money. But we’ve also now branched into promoting shows. We have a tour that we’re going to be announcing soon.

And to answer an earlier question, you have to have a brand name that’s about comedy. The comedy world is very insular. To have just called it 604 wouldn’t have made any sense. That’s why we made it a separate division.

How are you able to still practice law and manage artists, run a label, and be in business on other ventures with some of your artists? Are you bound by any Law Society’s ethical codes or do you simply use your own judgment when it comes to potential conflicts of interest?

I think so. I would never be the lawyer for a client I manage. You just can’t do that. The thing is, because I am a lawyer, certainly my clients often ask me for advice from a legal perspective, but any artists that’s on the label, any artists that’s on management company, they have their own lawyer. That’s important to me. I would never want anyone to feel they were taking advice from me that somehow affected my own interests. That’s just wrong. I’m very careful about that. The only one that’s maybe a little bit like that is Chad because we’re also business partners, but that was all done with lawyers. Twenty years in and we’ve never had a problem. But Chad’s definitely done things to help the label, big time. He produced that first Theory record and he brought in My Darkest Days, Thornley, Faber Drive. Simon Clow. He’s not involved in the day-to-day running of the label. I don’t think he could even name our employees. It’s not his role. It’s not his job. But if I need him for something, he is always there to help. He did a collab with Josh Ramsay on his solo album and very recently brought in a new act that we are looking at.

You had mentioned at the start of our conversation “the Hedley thing.” We know Jacob Hoggard, the band’s singer, was convicted for sexual assault causing bodily harm and sentenced to five years. He’s out on appeal and there is another sexual assault trial this fall. What do you mean by “vocal about the Hedley thing”?

I mean the allegations of sexual misconduct against Jacob Hoggard, but also the lack of accountability for those who enabled the conduct. I’ve commented about it on Twitter. Look, Jacob went to trial, Jacob was convicted, and the criminal justice system did what the criminal justice system does. As a former criminal lawyer, I believe in our system, and that guilty people are usually found guilty. And I believe justice was served, based on the facts that I know from following the case. What bothers me about it is there are people who turned a blind eye to that conduct, and people who enabled and even facilitated that conduct. Some of these people still work in the music business and have not been held to account for their roles in this horrible story. The trail of breadcrumbs is massive and stretches back some 20 years (for example, as outlined in the Exclaim! article about an incident at the Embassy in London in 2005). But apparently the music industry has no interest in following that trail, however concerning. It’s depressing, really.