BY KAREN BLISS

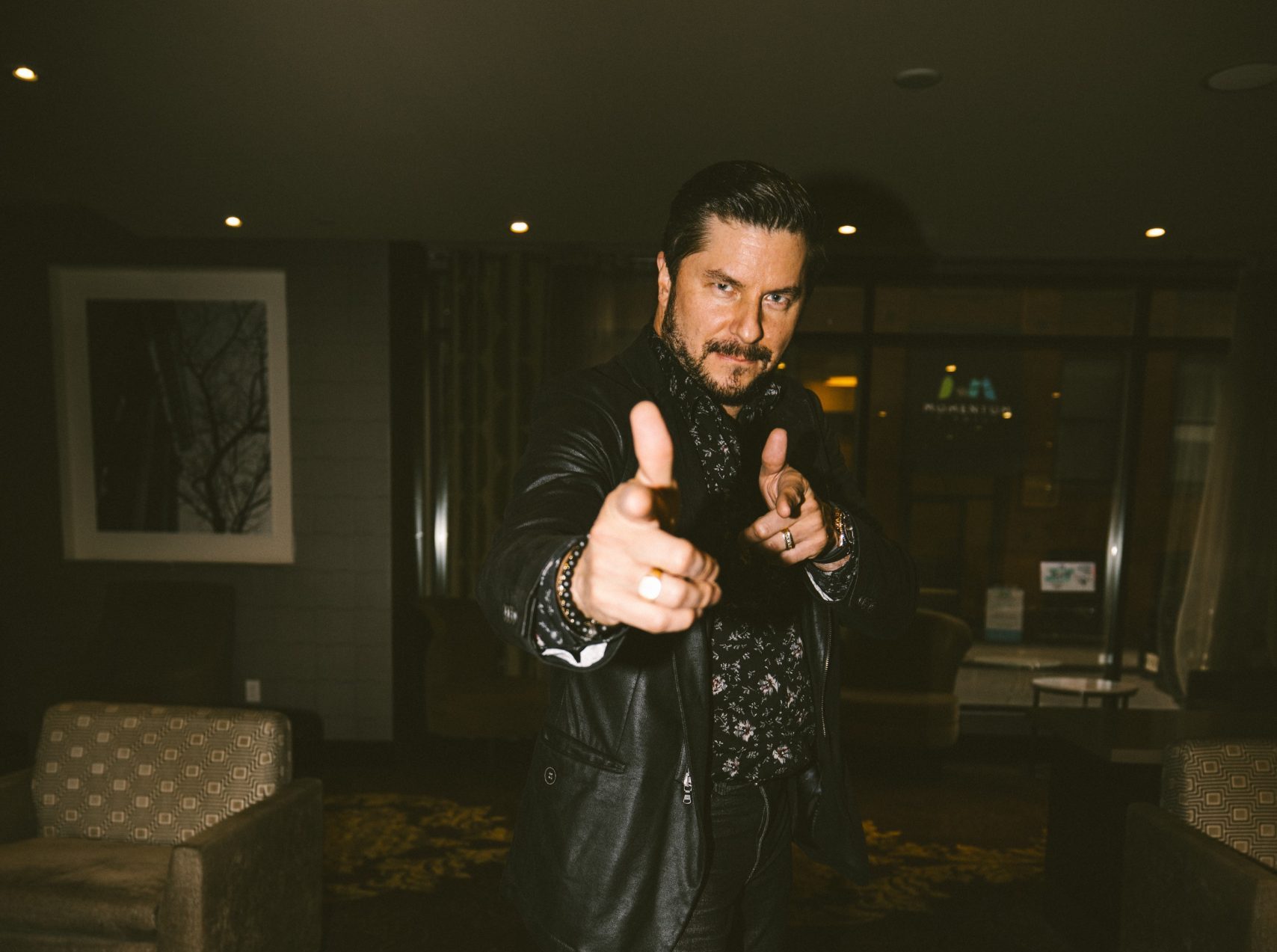

He goes by Chief. Many people might not even know his real name: Kevin Zaruk.

He’s been Chief ever since he started working in the Vancouver clubs in the early 90s, through tour managing and front of house for a-then unsigned Nickelback to a quarter-of-a-century later managing the rock band with catalogue sales of 50 million albums as they prepared to put out a new album, Get Rollin’, and find out if the world still cares.

They did — earlier this year, Nickelback was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, hit the road, and crossed with yee-haw success into the country market.

Through his company The Core Entertainment (TCE), Chief also manages Valley, Josh Ross, Bailey Zimmerman, Nate Smith, Dillon James, Gavin Lucas and Rachel Wiggins. TCE also reps four producers, Austin Shawn, Matt Geroux, Dipper and Marty James.

His enthusiasm for the business is still intact and his vision fresh. He founded TCE in 2019 with former Fund by First Access Entertainment managing partner Simon Tikhman. The management company is in partnership with Live Nation, and the newly created label with Universal Music Group. Born in Calgary, he divides his time between Los Angeles and Nashville.

In a July statement announcing the records division, UMG’s chairman and CEO Sir Lucian Grainge, said, “We love building upon our entrepreneurial culture, and are so pleased to welcome Chief and Simon who have a reputation for identifying some of the industry’s most promising artists. We look forward to helping them grow their roster and drive global success for their artists.”

Chief sat down with Making Noise in Toronto, following the world premiere of the documentary Love To Hate: Nickelback. He talks candidly about taking a chance 15 years ago to leave a guaranteed pay cheque for the chance to build a career-defining business of his own and make his mark as an entrepreneur. And how did he end up managing Nickelback?

You’ve been Chief as long as I’ve known you. Does the nickname date back pre-Nickelback?

Prior to Nickelback, since I turned 19. I was working in clubs as the stage tech. At the time. my mentor was a guy by the name of Kenny Turta. He called everyone Chief, like saying pal, dude, buddy etcetera, He was a front of house engineer at all the local clubs in Vancouver and mixed all the biggest bands. So, he would yell to the stage all the time at me and say ‘Chief, give me a mic check. Chief plug that mic in. Chief move that mic…’By the end of the night, all the bands would thank me by calling me Chief and assumed it was my real name. Then, I would see those bands again a few weeks later and they all called me Chief. It stuck.

How did you meet Nickelback?

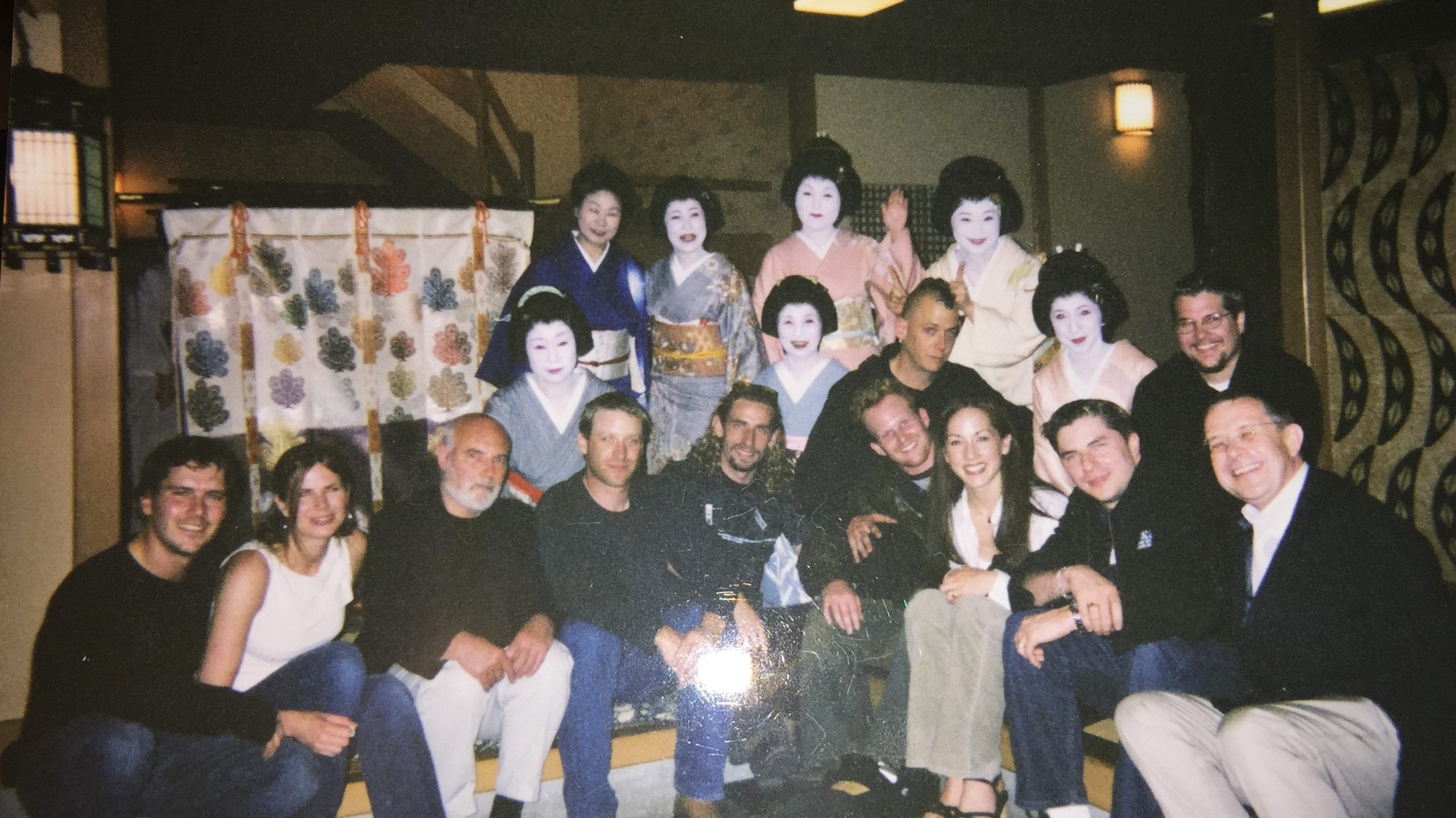

I went to Vancouver’s Columbia Academy after graduation to become a recording engineer and producer. My first-ever project I worked on was Nickelback on their first demo. That’s how I met the guys and they asked me to do their live sound. The adrenaline and the excitement were so much more inspiring than sitting in a studio that I then switched to doing that.

You started tour managing Nickelback in very early days. What do you have to be able to adjust or handle when faced with a career trajectory that big?

When we started, it was the four guys and me and the guitar tech in a minivan and a trailer. I want to say five years later, we were 18 trucks, 14 buses, and selling out every arena in North America. So it did happen very quickly. There’s a couple things. You have to be able to learn on the fly. You’re going to make a lot of mistakes; it’s just fact. But, the most important thing is you learn from your mistakes. My favorite quote from [football great] Tom Brady is there’s only two things that happen in sports, you win or you learn because when you lose that’s when you learn the most. And how you become successful is taking what you learn and applying it and not doing it again. The rise taught me so many things so quickly, but it taught me to learn from your mistakes and then just get better. And how can you constantly improve and improve every day? My brother told me this quote one day, he said, ‘I don’t wake up every day trying to make a bad decision. I don’t wake up every day trying to make a mistake.’ Everybody out there is trying to do the right thing or what they think is right or do the best at their job or do the best to their capabilities. So, if you can recognize that when somebody makes a mistake, whether it’s you or somebody else, you talk about it, you learn from it, and then you move on and you help each other. It’s not a matter of you screwed up, you’re gone, you’re fired.

Let’s talk about that because what I do see with Nickelback is their team are like family.

Very much so.

People have been with them almost from the start. [Booking agent] Ralph James, [publicist] Charlotte Thompson. [lawyer and Kroeger’s partner in his label 604] Jonathan Simkin. You.

And they have some of the same crew they’ve had since day one. It’s not always up to that person if make a mistake, to be able to stay and learn. You have to have supportive bosses to allow that and take you with them. The people that stayed the longest are the people that learned and adapted and made less and less mistakes. There are people, unfortunately, that don’t learn and they do make repeated mistakes. And those are the people you have to let go or you have to replace or you have to have another conversation and say, ‘Maybe this just isn’t for you. Maybe the road isn’t for you. Maybe the music business isn’t for you. Maybe these hours aren’t what you’re built for.’ Some people, just because you want to do something, doesn’t mean you can do it.

We also see with some artists, when they start out, they have a friend as a manager who takes them so far and gets tossed later for someone bigger and more experienced. Loyalty isn’t always there.

Yeah. One thing about the music business, we saw with Nickelback, any new artist, it always starts out as fun. Chad [Kroeger, Nickelback’s frontman] always says, ‘I didn’t start a band to do things I don’t like; I started a band so I can write music and play music because that’s what I love.’ It’s easy in the beginning because there’s nothing else to do, but, as you get bigger and more successful and more pressure and more money, and all of a sudden your life changes, it does become a business. It’s not just all fun and games and a party because if it does become that, then usually your business suffers. So, then, all of a sudden, you’ve got that turning point where there’s too much at stake. All of a sudden, I do need people that do their jobs the best that they can. There’s too much money on the line. There’s too much at risk. And then the artists need to accept it as a business. This is now what we do. This is how we make a living. This is how we pay our bills. This is how we put our kids through school. It’s still fun, but there is that turning point where we can’t afford to make mistakes. Thankfully, in the beginning, with Nickelback, I made lots of mistakes doing live sound and tour managing, pulling up to the wrong venue or having a terrible show and it didn’t matter because there was less at risk. But, all of a sudden, you can’t pull up to the wrong venue in an arena [laughs] and not load in in time, and it’s a domino effect. So there is that turning point, where we all were like, ‘Oh, you’re getting paid a lot of money to show up and play a show and put on a perfect show.’ The days of having drinks before the show or being hungover the next morning or being tired or showing up late, you just can’t do that. And if you do that a couple times, either you lose your job or if the band does that, all of a sudden, promoters aren’t going to pay you. They’re like, ‘We can’t rely on that band, so we’re not gonna pay ’em.’ So, there is that moment, where we all look at each other and go, ‘We have to take this seriously.’

At some point, you stopped tour managing for one of the biggest rock bands in the world and decided to start your own company. Why did you make that decision?

I was with the band since ‘96. So 2004, the band was at its peak. We were selling arenas. I was tour managing, doing live sound, and the guys were paying me as good as anybody out there. A lot of jobs, there’s a cap, there’s a ceiling, and I’m watching everybody else around them, including the guys, buy new homes and drive fancy cars and make a lot of money. And there was really nowhere else I could go. The guys were taking a year off and were like, ‘If you want to make more money, then you might want to change your career path because we can’t pay you more. We’re already treating you great.’ And I am sitting there looking at their manager, Bryan Coleman, who I love, and I’m like, ‘Damn, I want to do more of what he’s doing.’ I was on the road; I knew touring; I knew the record side; I knew the radio side; I knew the promotion side; I felt like I could become a good manager. So they took a year off, and in that year they’re like, ‘Go and find a band to manage.’ and a band called Hinder from Oklahoma reached out to [producer] Joey Moi and said, ‘We love Nickelback. We want to come to Vancouver and record some songs.’ So they drove up to Vancouver. I went and met them in the studio and hung out, loved the music. They didn’t have management. They’re green. And I’m like, ‘I’d love to start managing you guys.’ We formed an agreement [2005], and I went to Oklahoma, saw them play, and from that day on I loved doing management.

Two-thousand-and-five is when the record came out and Nickelback was now going on the road. So I went to the guys and said, ‘I want to do management.’ And Chad and the guys were like, ‘Well, why don’t we bring Hinder out on the road? So you can continue to work with us and you can continue to work with them.’ So for the next two years, I was tour managing Nickelback, front of house for Nickelback, and managing Hinder. Somehow, it all worked, up until about 2007, where Hinder just blew up with [the hit single] ‘Lips of An Angel.’ All of a sudden, the time and the money and their energy was everything I wanted. I wanted to do that. And the guys knew it. The writing was on the wall. So I left shortly after that, around 2007, and then that’s when I really started my own company, Chief Management. I’m ready to now do this full-time. All of a sudden, I had Jessie James, who’s now Jessie James Decker, and then I had Ace Frehley and Jason Newstead, then a band called Jet Black Stare. I just started getting clients and really loving what I was doing. That was the beginning of I want to manage bands.

Meanwhile, you kept in touch with the Nickelback guys all this time?

The whole time. They’re always super supportive. Always kept in touch. We’re like brothers. They were doing their thing; I was doing my thing. We always hung out, for birthdays, Christmases.

Now, you are entrenched in the country music world. How did that happen?

What happened was in 2010, most of my acts were in the rock scene, but 2010 basically the rock scene started to die. I was also managing Joey Moi, as a producer. Joey and I get a call from Seth England in Nashville, [CEO] at Big Loud Publishing and Big Loud Shirt. And he said, ‘We have an artist who loves Joey’s work. Would Joey be interested in mixing a song?’ We’re like, ‘Absolutely.’ So they sent a song, Joey mixed it, they called us back, said he wants to work with Joey on his new record. Would you guys come to Nashville? So Joey and I go to Nashville and it was Jake Owen. And it was ‘Barefoot Blue Jean Night.’ Joey ended up with four No. 1s off that single, mixed eight songs, produced four. This was in 2010 and we never left. So Craig [Wiseman] and Seth sat with Joey and I and said, ‘What do you guys think about starting a company? Nobody in town develops artists. They just sign and put them out and hope for the best. You guys develop artists,’ because Chad, Joey and I had developed Default and Theory of Deadman and My Darkest Days.

They’re all rock acts. What was your affinity for country?

There was no affinity for country at all, to be honest with you. But the basic concept of developing an artist was still the same. Make sure they can sing, give them vocal lessons, make sure they can play, give them guitar lessons or piano lessons. Teach them how to write, put them in rooms with people that write great songs, teach them how to be great doing interviews and press and PR, teach them how to be great live, how to move, how to talk to the crowd. Regardless of what genre, the idea of developing artists is something that came very naturally and we loved doing it. I think we loved it so much because we did it with Nickelback. We went through all the things to get that band to where they needed. So we didn’t really care about whether it was country or not. We just liked the idea of doing it, period.

So Joey and I were like, ‘We love this idea.’ I knew management, they knew publishing. Joey knew how to make records. They had a building, they had an office, they had a studio. So, we were like, ‘Let’s start this company.’ Joey was Mountain View Studios [with Kroeger], and they were Big Loud. We first called the company Big Loud Mountain; that was the name of our joint venture. We put $20,000 into our new venture so $80,000 [from Zaruk, England, Wiseman, Moi] and we’re like, ‘Let’s go sign an act.’ And Seth is like, ‘I got these two guys in town who I think are really good. They’re up and coming young songwriters no one really knows about them, but I’ve been keeping tabs on them. We should go see them.’ And we went and saw them, and it was Brian [Kelley] and Tyler [Hubbard] from FGL [Florida Georgia Line] and they played this little club show and we loved it. We brought them in the office the next day and we said like, ‘We wanna sign you guys to management and publishing.’ And they’re in.

Were you still managing all those other acts?

All the other acts are now basically gone. They’d either broken up tor they’d gotten dropped. Just one by one, we’d moved on. So we started this venture. Enter FGL and that was the beginning for us, now a new management company, no longer under Chief, but under Big Loud. Then, we started signing acts. We signed Chris Lane, and then we brought Dallas Smith over to our company and then Mackenzie Porter and it just grew from there. Then, in 2018-19, the management focus started being ‘How can we branch out and become bigger? How can we just not be country? How can we branch out of Nashville?’ And Joey and I, not being from Nashville, always were like, ‘How about LA and New York?’ We then partnered up with Maverick, which was Live Nation. Live Nation basically funded Maverick and it was run by Guy Oseary. The idea was sort of like Red Light and Roc Nation.

Did you approach them?

No. Clarence Spalding in Nashville, who’s got [Jason] Aldean and Rascal Flatts, a great roster. He approached us and he’s like, ‘I am in Maverick. I’m with Live Nation. I want you guys to come and meet and see if this is something you guys would be into.’ It was perfect timing because we were looking to expand our personal roster of other managers.

Building a company on your own and then taking a partner of that size, what are you giving up and what are you gaining?

The concerns of doing any partnership or JV is simply financial. You are giving up a piece of your pie. What you have to do is bet that with your new partners the piece of the pie will grow so big that the piece you’re giving up is minor compared to the piece you’re getting back.

Do you always have an out so that if it doesn’t work, you get it back what you built?

Yes and no. You do, but within a time. It might be a three-year deal, it might be a four-year deal, it might be a five-year deal. Everyone has different parameters. It might be you can have it back if you’ve recouped X amount. It just becomes a math equation. But for someone like Clarence or somebody like us, it’s like signing a record deal, truthfully. You kind of get an advance on what your projections are going to be, and then if you pay that off, you can either get another advance or you can leave. For us — and everyone’s different — we took that advance to then go start Big Loud Records. For us, it wasn’t that we wanted to take money off the table, we were fine, but if we can take a bigger chunk now and then use it to go start records, which was our dream, well now we’re just funding it without actually using our own money right. That would’ve been 2017.

I’m no longer with Big Loud. So 2018, 2019, we start this whole thing with Maverick and it’s all great. Then, our lawyers connected me with my now business partner, Simon Tikhman, who was over at another management company called First Access and was looking to leave that company to do something else. He didn’t know what. Our lawyers, Joe Carlone and Peter Paterno, were like, ‘You guys should just meet; maybe there’s something.’ So I went and met Simon, smart young guy, very connected. Thought the same [as me], same ideas, same vision, global acts, loves music, loves the idea of developing acts. So I said, ‘We should talk with Michael Rapino. Maybe you start your own thing at Live Nation?’

What are Simon’s skills?

His background is in investments. That is what, at this other management company, he was doing. He’s working with athletes and artists, doing alcohol deals or brand deals or whatever. That’s where his introduction into the music world was, but then quickly realized — like what I did — saw the management side of things every day and was like, ‘ I love that side,’ and became passionate about it. So as he and I were developing our friendship, and figuring out if there is a way we could work together, and is it Maverick? Is it Live Nation? there was now a shift in Big Loud where Florida Georgia Line, after 10 years, was now wanting to leave. And not on bad terms, actually on great terms, but kind of like Nickelback leaving Bryan Coleman, sometimes you feel like a change. Maybe we’re stale, maybe we’re not getting what we want. So that was our biggest client. All of a sudden, now the management value was going to be much smaller than publishing and records.

Seth now wanted out of the management game and wanted to go be the president of Big Loud, Craig is running publishing and Joey’s making records. So they’re looking at me like, ‘You’re running management and it’s now becoming the least important part out of the rest of the businesses.’ And truthfully, as we all know, it’s the riskiest part because bands can quit or get canceled or break up or you can get fired. So there’s no long-term and there’s no ownership; it’s not like how you can sell a record label for two, three, four billion dollars; you can’t sell a management company because it’s only worth what it’s worth today. You get fired tomorrow, it’s worth nothing. So, I think Seth, Joey, and Craig really turned on their business hats and went, ‘Wait, this, this piece of the business no longer really makes sense for the big scope.’ So they had decided that they wanted to part ways. Not my decision, but at the same time, I understand why they thought that, but also I think maybe they didn’t see the value of what the management company had in the big scope. It was a big part of what everything else was feeding.

So, as that was happening. The exact same time, I now go and sit with Simon and Michael in LA and we have this great three-hour meeting, and Michael’s like, ‘I think you’d be great. Let’s figure out what you want to do. You should come to Live Nation. You should work here. Let’s have more conversations. And then I’m like, ‘This is great.’ And I said, ‘By the way, Michael, also looks like I’m not going to be at Big Loud anymore.’ And he’s like, ‘You guys should just partner up and start your own company.’ It was that quick. We all looked at each other and were like, “It’s actually not a bad idea.’

This was now a week before covid, so in that week I’ve now basically parted ways with Big Loud, getting ready to figure out what this new venture with Simon’s going to look like, and then covid hits and everyone thinks it’s going to be one week, then two weeks, then two months and kept waiting for it to end. And a couple months in, I was just like, ‘We gotta get going. Us sitting around isn’t doing anything. We’re start trying to launch a new company. They’re still artists out there. They’re still making music. They’re still releasing music. They’re still releasing content. Besides touring, there’s work to be done.’ And we started going to Nashville. That was the truly the beginning. We started signing acts during covid and we got record deals and we got publishing deals and everyone was still working, just obviously under different circumstances, and live streams and all the things that everyone is trying to wrap their heads around. That was the beginning of The Core about three years ago.

There will always be managers. Pretty traditional type business model. But the industry is changing more quickly than it ever has in its history with new technology integrations and ways to break artists and seek out different revenue streams. What are you looking at that’s unique?

Look, there is no magic trick.

What are people not getting? Our industry is very slow because for many years it was run by people that were very comfortable at the top and fought technology and advancements. Now there are a lot of young people creating their own companies or infiltrating old.

I think you’re seeing it in a lot of businesses in the world. You said it, the music business is slow. And I think people get very comfortable with what has worked. They don’t like change because change is hard. Change is unknown. You can make changes and it might not work. And are you willing to take risks because with things moving so quick, what works today might not work tomorrow. And, I think, with a lot of the majors being now even on the stock market, they can’t move as quick as independents can move. They can’t move as quick as managers. Managers can sit there and go, ‘I got a song today. I’m gonna put my artists in the studio tomorrow. We’re gonna mix and master by Friday. We’re gonna announce on the weekend. We’re gonna shoot content and it’s gonna be up next Friday.’ And then you try to tell a record label we’re gonna record and release the song in a week, it just can’t happen. So, and the truth is, it, it now can happen. The only reason it can’t happen is because they have systems in place that allow it not to happen. And when you see things being consumed so fast, an artist have moments — whether you want to call them viral moments or TikTok moments or whatever it is — when something hits and you have the attention of your audience, you have to grab it and use it and move quickly. So a big part of what we do, we move quickly. And in order to know when and how to move quickly, you have to pay attention to socials. You do have to pay attention to analytics. You do have to pay attention to what’s working and what’s not.

And when I say what’s working and not, I’m not saying what trends are working and following trends. I’m saying that within your artist, and within their brand, and what they want to do and how they want to say it and what they want to release, you say it. The days of faking and pretending are gone. you can’t try to be someone you’re not. You can’t write a song and then say, ‘I believe in it.’ And everyone goes, ‘No, you don’t. We don’t believe in it.’ But what you can do is sit down with an artist and be like, ‘Who do you want to be? What voice do you want to have? What songs do you want to sing? Who’s our market? Who’s our demo? Who’s our audience? Where do you want to see this?’ And you take all that information and then you go write music, or find songs that are exactly on brand with who that artist is. Now, when you put a great song, with a great brand, and it’s real and it’s authentic and you put it out there and then you watch the reaction, and if it reacts you’re like, ‘This is working. People are loving what you’re doing and they’re believing what you’re doing.’ And now the artist is loving it, so they’re going to believe in it and do it even more and do an even better job.

I think where labels, and where we have the advantage right now, is we dig in so early that before we put out a song, the thought and effort and conversations and songs and lyrics that we’ve put sometimes years in before you hear an artist, that when it comes out it we tell all of our artists if it doesn’t work, it’s not because we collectively didn’t do all the right things. The one X factor is we can’t make fans like it and we can’t make fans buy it and we can’t make fans choose to do anything we want. But what we can do is put out a product that if it doesn’t work, the artist is like, ‘I did everything I could and I’m proud of it.’ As a company, we go, ‘We did all the right things. We marketed it right. The content was right. The songs are great. We put it out. We spent money. We did all the things. It didn’t work’ and then no one can blame anybody or point fingers, but you have to make sure it’s right. And you have to make sure it’s on brand. You have to make sure it’s believable and you have to put out great music. I think that we have also gotten lazy where people are like, ‘Well, you just keep putting out music until something sticks.’ You can put out 20 songs and none of them stick and you’re done. And if they’re all 20 mediocre songs, they’re not going to stick. Things don’t stick if they’re not great; things stick because they’re ultimately great.

I heard labels signed 20, 30, 40, 50 people from TikTok during covid and now they’ve dropped all of them because didn’t know if they could sing; they didn’t know if they could perform; they didn’t even know if they’re good people. They just like, ‘oh, is this a moment? Oh, you’re getting a lot of likes. We’re gonna sign you, put it out and see what happens.’ Guess what, 99.9% of that did not work. And I just think that’s not what the consumers want.

Finally, during covid, 2021, Nickelback was looking for management again. Actively meeting with managers and they came back to you. How did that happen?

Interesting enough, when they had parted ways with Bryan Coleman, and again, for no other reason than kind of like FGL it’s just time for change for all of us. They had gotten stale, they’d sort of hit a wall, they kind of lost their drive. They’re like, we don’t know what to do next. Interestingly, the first call was to me to tell me that they were, were moving on from Bryan Coleman, but my name was not in the hat. And the reason they basically said, ‘We’re friends. We’re family. The idea of now working together, we are afraid is going to put that at risk.’

And what did you say? Did you agree?

You know what, I understood. And, also, I didn’t want to put pressure on them. I wanted it to really feel like this is the best thing.

You didn’t say, ‘Hear me out’ with a PowerPoint?

I didn’t say, ‘Let me convince you. Truthfully, I was also shocked at the call because they were with Bryan for over 20 years. So I didn’t ever think that they were going to leave him, and then call me and come to me. ‘m now really established in the country Nashville scene. It wasn’t even a thought.

Their career could have gone either way.

They hadn’t toured in five years. They’d put out no new record. They were not on social media. Their last tour wasn’t great. Their last record wasn’t great. And the last European tour wasn’t great. So, when they called me to tell me that, I was like, ‘Great, good luck.’ They had then gone on and met with everybody. I don’t remember exactly how long the process, but I want to say it was at least six months, maybe even longer. I wasn’t asking. I wasn’t checking. I just assumed they got another manager and they’re off. And then Chad called me one day. They had gone through all the meetings, picked another manager, been with him for like a week, and it just didn’t feel right. They were then coming back to LA for a new round of meetings at Sunset Marquis, and he was like, ‘I want you and Simon to come in, but we want this to be a proper meeting. We want you guys to come and tell us, if you were to manage us, what would this look like? Let’s forget about friends aside.’ We’re like, ‘No problem. We’re happy to come in.’ So as we’re coming in, [Redacted] is leaving. We walk in and there’s all these Nickelback books on the table that these management companies have put together of analytics and your history and your sales and this and that, and here’s what we do and blah, blah, blah. And they’re just sitting on the table. So Simon and I sit down and they’re like, ‘So where’s your guys’ book?’ And I’m like, ‘We didn’t put together a book.’ And Chad’s like, ‘Thank God, because If I have to read another one of these!’ He’s like, ‘I’m not interested in the book. I’m interested to hear from you guys.’ And we sat there and we had a very open, honest conversation for an hour and a half. And they’re like, ‘We have a new record. How would you promote it? What do you guys think we should do? What do you think we’re missing?’ Blah, blah, blah. And the truth is, what we knew nobody else knew. And what we knew was being in Nashville, and working with all these young acts, every single act we were working with — whether it was Morgan [Wallen] or Hardy or Jake Owen and then Nate [Smith] — were obsessed with Nickelback. They were all heavily influenced by Nickelback. They didn’t give a crap about the hate. They were never a part of the hate. Nashville didn’t even know there was a hate thing.

What we knew was there was an audience out there that love Nickelback and were like, ‘We’d do anything to get in a room to write with Chad. He was one of the greatest songwriters, one of the greatest vocalists. I grew up listening to Nickelback,’ blah, blah, blah, blah. So it is an easy pitch for us. It’s like, ‘Guys, if you give us the keys, if let us introduce you to an audience that you’ve never tapped into and an audience that adores you and admires you and looks up to you, and you agree to come out of your comfort zone and get into another zone, you’re going to be accepted and your eyes are going to be opened up to a whole new genre that actually isn’t that far from ‘Rockstar’ and ‘This Afternoon’ and songs you’ve done and recorded.

And on top of that, we can open up TikTok, which you guys have never been on, and we can show you daily videos of people posting Nickelback clips and going viral, of people dancing to your songs. And everyone’s like, ‘Why the hate? We love this band’ and they’re all 20-year-olds who are just like, ‘I love this, man. I just discovered Nickelback for the first time.’ It’s like, ‘There are two audiences out there that you guys don’t even know about, that if you tap into and let us lean into that, it’s going to be a gamechanger.’ And they were uncomfortable. Yes; unknown, yes. Was it going to be guaranteed? No, but let’s try it. We were the first managers of all their meetings to be like, ‘Forget the old, because anybody could do that. Anybody could drop you guys on tour with Shinedown and Three Days Grace and go and take your songs and drop them on rock radio and go. You’re going to get the same results. It wasn’t Bryan Coleman, right? Any manager’s going to come and do the same thing. You guys gotta do things differently. And we think we’re the team to do things differently. We have a young staff and we understand socials and TikTok. And we left that and they’re like, ‘You’re in.’ Let’s do it.’

They headlined [Canadian country music festival] Boots and Hearts in August and it just worked perfectly, and Stagecoach in Indio, California, is next April.

For this tour, that they’re on now, which is their biggest tour since 2010, we brought in Brantley Gilbert, a country act who has a rock edge to him. And then we put Josh Ross, who’s ours, a country guy, on as opener. Then the idea of doing some of these festivals is Hardy’s on them and Bailey’s on them. They’re doing country rock festivals. And they’re really tight with Jelly Roll now. And, all of a sudden, you see love. You see a show with Hardy, Nickelback, Bailey, Jelly Roll. There’s nothing weird about it. You’re like, ‘Oh, this all makes sense.’ You watch them on stage and you go, ‘This is perfect.’. And you look at the audience and you go, ‘It’s the same audience for all of them.’ So it’s happened very organically.

But when I say organically, with a purpose, right? It happened when we released music, we released the song to rock; we released the song to Hot AC. We make sure we’re still doing all the things to make the rock fans happy. But, look, Nickelback always got played on pop, Hot AC and rock. They always crossed all the genres. The only genre they never dipped into is country. But country is now rock. It’s an easy thing. It’s not a stretch for them to be accepted.

And, we haven’t announced it yet, but they got a bunch more things that they’re doing in Nashville next year. A bunch of exciting shows that are festivals that you’re going to be like, ‘Oh, I didn’t expect that.’ When we announced Stagecoach, their team over there said the three biggest responses were Morgan Wallen, Post Malone and Nickelback. So, it’s working and the guys are excited.

The band was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame earlier this year and the Toronto International Film Festival just premiered a documentary, Hate To Love: Nickelback. A big year.

The doc will be out somehow, somewhere next year. The band is rejuvenated, I think back better, as good as ever, and there are going to be so many exciting things coming next year. This isn’t a one and done and now they’re good. We are just getting started on a bunch of things that probably a couple years ago never would’ve been available or accessible to Nickelback because people frankly thought they were done. I actually think the guys might’ve even been questioning what’s left in the tank and now I think they realize there’s a lot left in the tank.